Fighting cyber threats from inside and outside of universities By Andy Baldin, VP – EMEA at Ivanti

Organisations of all shapes and sizes devote the majority of their cybersecurity efforts on in-bound threats, and whilst this logic may seem like it makes sense, given that a reported 60 percent of breaches involve external actors, it is not correct to view this as the main area of danger. Threats can also come from within an institution – employees often will, and sometimes unwittingly, infect their colleagues by sharing malicious data. This is a difficult enough issue to deal with in a workplace, but it can be an even bigger problem at universities.

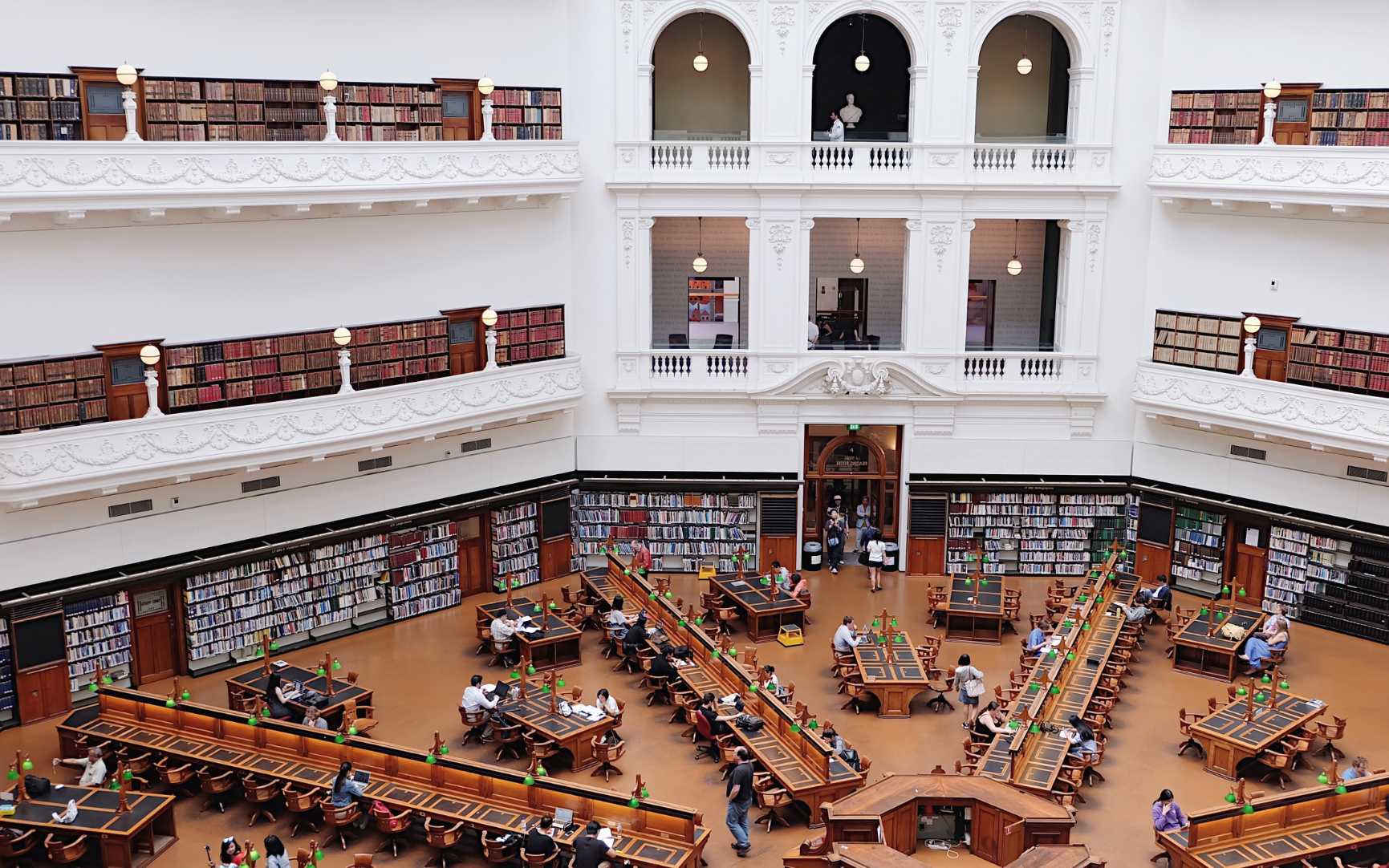

The complex structure of a university means that implementing a successful cybersecurity strategy can be extremely challenging for IT and security teams. Even between different universities, many variables – such as the number of network users, the number of departments, off-site network access, the nature of the work being done and whether the university is campus- or city-based – can cause headaches. One unifying factor among universities is that there will be hundreds, if not thousands, of students, staff and alumni accessing the network through a range of devices that can be smart phones, tablets and PCs running different operating systems, as well as games consoles and smart home devices. The devices in an office environment and its patch status can be appropriately managed with the right strategy. However, it is impossible to prescribe to students that they must use a particular operating system, device manufacturer or version status on personal devices.

It is evident that universities need to evaluate how they can best protect against the current security threat landscape as research shows that things cannot continue as they are. Jisc, (formerly the Joint Information Systems Committee) analysed the timing of 850 attacks in 2017-18, finding that they were largely concentrated during term-time. Importantly, the report concluded that cyberattacks against educational institutions often come from staff or students, rather than external hackers. One highlighted example saw what appeared to be a four-day cyberattack on a university which turned out to be the result of a student living in halls who had been attacked whilst gaming online. There is every chance that this student could have left the network completely exposed and vulnerable for subsequent attacks.

Similarly, there exists the threat of disgruntled staff and students who might want to attack a network purely to a disruptive end. These types of internal threats largely occur through distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. A DDoS attack is a malicious attempt to disrupt a server’s activity by overloading it with requests. To carry one out, an attacker will have to have access to a large number of machines and direct them to one web address. If you’ve ever tried to buy tickets for a high-profile concert as soon as they’ve been released, you’ve probably experienced the website being unusually slow. This is because an abnormally high number of machines are trying to access the same page, exhausting the server’s bandwidth limits. A DDoS attack is this, but mobilised by a single source who has gathered a range of machines and created a bot (referred to as a ‘botnet’) to clog up and crash the website by making hundreds of thousands of the same request simultaneously. DDoS attacks are not aimed at stealing data or infecting a network with malware but could, for example, be used by a student who wants to make it impossible to submit coursework on the day of a deadline or simply as a prank. To make matters worse, this type of attack is not a particularly complicated process that requires a lot of technical knowhow. In fact, many hackers sell DDoS services online for an alarmingly inexpensive cost.

One might then assume that an aggressive policy of monitoring and regulating network activity is the best way to fight against insider threats, but the other fundamental issue that must be addressed is the simple fact that the majority of the network users are paying for the privilege. They are not employees who, asides from an occasional glance at the news and Twitter, are expected to be spending their network time doing work. At a campus-based university, students and often staff will likely be spending the majority of their time doing non-work-related things on the network, whether that’s playing games or watching videos. There may be malicious actors, but it is unreasonable to simply restrict the digital liberties of students who are paying thousands of pounds a year in tuition and accommodation fees.

As such, the growing trend towards a heavily restrictive zero-trust network within organisations is not particularly viable. In its most basic terms, a zero-trust network architecture (as the title suggests) is based on the mantra of ‘never trust, always verify’. Before any network access request is granted, a centralised policy engine verifies the user, validates their device and limits access and privilege based on the user information on the central system. The main idea here is to use automated processes to keep a tighter grip on network activity. While this approach is gaining a great deal of traction with businesses, it relies on routine activities with devices that are familiar to the network – which is impossible to control with a network made up of user-owned devices. The university manager must instead create a system that is secure enough to protect users and the greater network, while also being aware of and appreciating the diversity of devices and activities going on.

One method for this that has seen great success across many universities including The University of Cambridge is the unification of different IT support divisions into one centralised service. Rather than the different divisions working on their own isolated tasks, implementing a unified University Information Services (UIS) department can provide cohesive IT support to tens of thousands of the universities’ end users and conform to ITIL best practices. Crucially, with a singular IT entity, a university will have a broad overview of all the network activity, making securing the system from within more manageable. With the deployment of a UIS department, the efficiency required for dealing with modern workloads is brought together with the necessity for a data security system that is effective at fighting both internal and external threats.

Cyber threats are on the rise and hackers are getting increasingly sophisticated. Universities, like all organisations, must be aware of this, but they are in a unique position in terms of their IT. The amount of activity and the range of devices active on a university’s network can be difficult to keep on top of for an IT manager, but it is not a lost cause. By unifying the different IT support divisions under one banner, universities will be better placed to keep on top of questionable activity and work in a more efficient way, without being overly restrictive to the students and staff who rely on the network for their work and entertainment.

For more information visit www.ivanti.co.uk.